Oregon 6A football may get the lion’s share of media coverage these days, but don’t sleep on those young men playing at the smaller enrollment levels. If Oregon history has taught us anything, it’s that truly great players can come from ANYWHERE.

Dante Rosario was one such great player. He had an eight-year career as an NFL tight end, but honed his craft playing for the legendary Dewey Sullivan, the state’s all-time winningest coach, at Dayton High School, a rural community of fewer than 3,000 people.

Many do not know that Rosario’s greatness in football almost ended before it started. Before his sophomore year started at Dayton, Rosario informed football coaches that he was going to concentrate on basketball. Sullivan sent all of his seniors with cars out to Rosario’s place and they persuaded him to stick with it. In his senior season, 2002, the 6-foot-4 Rosario was named 2A Defensive Player of the Year and also was First Team All-State as a running back for the state champs. In the state final against Amity, Rosario rushed for 126 yards and four touchdowns and also was everywhere on defense from his linebacker position.

Rosario also played basketball throughout high school and helped Dayton win two state titles in that sport. Recruited to play linebacker at Oregon, Rosario spent his career with the Ducks on the offensive side of the ball. In 2007, he was taken in the fifth round of the NFL Draft by the Carolina Panthers as a tight end. He had 116 receptions over his pro career with eight touchdowns.

In Oregon, smaller schools undoubtedly have fewer good players than those at the 6A level. The simple fact of school enrollment is the principal reason, though football players might not develop at the same rate at smaller schools for other reasons as well. Athletes at small schools usually play multiple sports and cannot specialize. They may have socioeconomic disadvantages that do not allow them to devote more time to football. And, with smaller paid staffs, they do not get as much dedicated coaching in the sport.

But while there are fewer good players playing on Fridays at the small-school level, there are great players and they most definitely stand out.

Take Rosario, for instance.

In 2002, Sullivan came to watch Heppner and Kennedy play in the first round and brought Rosario with him. Sullivan stopped and made small talk with Heppner coach Greg Grant.

Said Grant: “After the game my wife asked me who the coach and player were. I told her it was Coach Sullivan from Dayton and his best player. She looked at me and said, ‘You don’t have ANYONE that looks like that kid.’ I did not!”

The next week, Rosario was everywhere against Heppner.

“Fourth and 2—no problem—he would lead block or run it,” Grant recalled. “Get what they needed. We pulled out everything we could and he was there to stop it. A perfectly executed ‘Hook and Ladder’ -- he runs us out of bounds for just a 10-yard gain. It was impressive to watch, and humbling to play against.

“The most impressive thing about Dante Rosario though was how he conducted himself. He was humble, he was polite and he was someone who only brought attention to himself with his play. He was complimentary to our players during and after the game. We all became Dante Rosario fans that day.”

Rosario was hardly the only small-school hero to shine on much bigger stages.

Douglas High School sits 80 miles south of Eugene in the town of Winston and was where Troy Polamalu first started making a name for himself. Born in Southern California, Polamalu reportedly begged his mother to let him live in Oregon after visiting relatives there. He was a three-sport standout at Douglas. On the gridiron, he was named All-State as a junior when he rushed for more than 1,000 yards and had eight interceptions on defense. He only played four games in a senior season cut short by injury, but managed almost 700 yards rushing and nine touchdowns during that span.

Polamalu returned to SoCal to play collegiately at USC before being drafted in the first round as a safety by the Pittsburgh Steelers. In 12 years in Pittsburgh, Polamalu made the Pro Bowl eight times and twice was on Super Bowl championship teams.

Born in the eastern Oregon city of Ontario, a city of 11,000 near the border with Idaho, Dave Wilcox played his high school ball for Vale in the late 1950s and was part of state championship teams in 1957 and 1958. Wilcox played on the line but made the transition to outside linebacker in the NFL. He played for the San Francisco 49ers for 11 seasons. Nicknamed “The Intimidator” for his bruising style of play, Wilcox went on to play in seven Pro Bowls.

Bob Lilly came to Pendleton, also in the eastern part of the state along the Umatilla River, from Texas in 1956. He gained All-State honors in both football and basketball during his time with the Buckaroos and was a state champion in the javelin as well. He played collegiately at Texas Christian University and was a two-time All-America performer for the Horned Frogs. In 1961, Lilly was the first-ever draft choice for the new Dallas Cowboys franchise and enjoyed a 14-year career on the defensive line as “Mr. Cowboy.” Lilly was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame in 1980. He has kept his relationship with Pendleton close and come back often.

“Truly one of Oregon’s great treasures,” said Pendleton sports historian Tom Melton.

Ever hear of Russ Francis? He was Gronk long before Patriots tight end Rob Gronkowski was even born.

A massive man born on Oahu, Francis started his high school career in Hawaii before moving to Pleasant Hill, a small town in Lane County near Creswell. Francis played football for the Pleasant Hill Billies and was a decathlete. In 1971, he set the national high school record in the javelin, a mark that stood for 17 years.

Francis played only 14 games in college at the University of Oregon, but that did not deter the New England Patriots, who took the big tight end in the first round with the 16th pick overall. Francis was a three-time Pro Bowler with 393 career receptions and was a pro for 14 seasons. In 1984, he won a Super Bowl ring playing for the 49ers and had five catches for 60 yards in the big game.

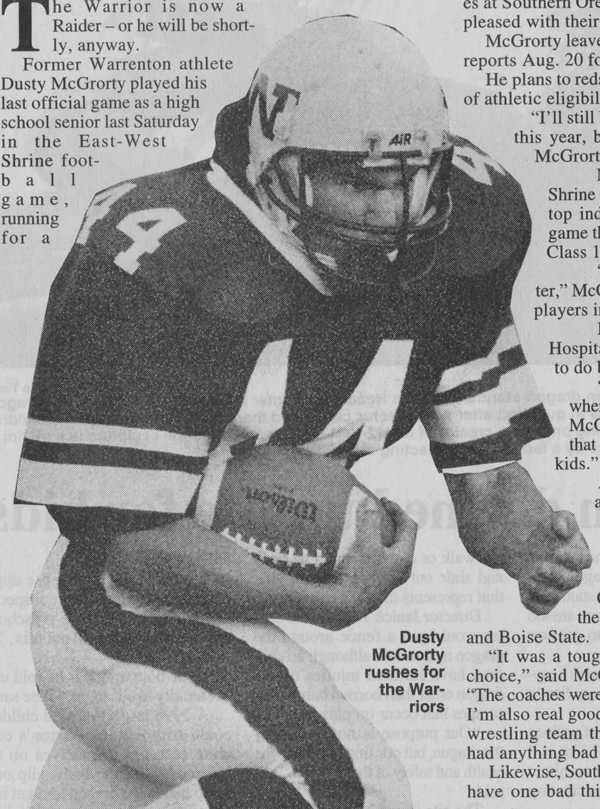

Dusty McGrorty was a three-time NAIA All-American and the first player from Southern Oregon University to ever play in an NFL game. But before he was playing in Ashland for the Red Raiders, McGrorty was an All-State running back and linebacker at Warrenton, located in a small coastal city of 5,000 near Astoria. McGrorty finished his high school career with 4,723 yards rushing and 65 touchdowns for the Warriors. He was the 1998 2A Oregon Offensive and Defensive POY as a senior, when he was also an undefeated state wrestling champion at 189 pounds.

After a stellar career at SOU, he signed a free agent contract with the St. Louis Rams within minutes of the conclusion of the 2004 draft and played running back behind superstars Marshall Faulk and Steven Jackson. McGrorty’s NFL career spanned one game. In the 2005 pre-season, McGrorty was released. But he had played in an NFL game, beating the odds that for every 100,000 high school players, only 215 (0.2 percent) will ever make an NFL roster.

Across the bridge from Warrenton is Astoria, where Jordan Poyer was all-everything from 2005 through 2009. He lettered three times in football for the Fishermen and was 2008 4A Offensive and Defensive Player of the Year, the same year Astoria won the state title. Poyer also lettered for four years in basketball and four years in baseball, helping Astoria win state titles on the diamond in 2006 and 2009. An All-America defensive back for Oregon State, Poyer was selected by the Philadelphia Eagles in the seventh round of the 2013 NFL Draft. He currently is the starting free safety for the Buffalo Bills.

The city of Stayton sits 14 miles southeast of Salem and is where Travis Lulay got his start. Playing quarterback for Regis Catholic, he took the Rams to the 2000 and 2001 2A finals and was Oregon Offensive POY as a senior. Lulay went on to have a record-breaking career at Montana State and played in NFL Europe for the Berlin Thunder and signed NFL contracts with the Seattle Seahawks and New Orleans Saints before finding his home in the Canadian Football League with the BC Lions. In 2011, the Lions won the Grey Cup behind Lulay, who was not only named MVP of the game, he also was named league MVP that year. Now 35 years old, Lulay continues to play for BC and has thrown for 1,845 yards and eight touchdowns this season.

Finally, a story about Oregon’s favorite small-school football sons would be incomplete without mentioning quarterbacks Kellen Clemens of Burns in Eastern Oregon and Derek Anderson of Scappoose along the Columbia River between Portland and Astoria. Born nine days apart, Clemens and Anderson have seen their careers intersect many times at the high school, college and NFL levels.

Clemens, the stepson of an Oregon rancher, starred at Burns not only as a signal caller but at safety and as a punter and kicker. He led the Hilanders to the 1999 3A state final, won the Gatorade Player of the Year Award in 2000. He graduated as the state’s all-time passing yardage leader and threw more than 100 touchdown passes.

Anderson, from a logging community of about 5,000 approximately 300 miles away from Burns, starred for the Indians in both football and basketball and was named state Player of the Year in both as a senior, when he led the Indians to the state title in football.

Clemens and Anderson met for the first time in the state semifinals in their senior seasons, with Scappoose winning 46-26 on its way to the state title. Clemens, who is small and athletic, and Anderson, who is tall and rifle-armed, went on to star at Oregon and Oregon State, respectively, and each won one game playing against one another when they both were starters. Clemens and Anderson played many years in the NFL, mostly as backups. Anderson is on the Buffalo Bills roster currently while Clemens last played for the Los Angeles Chargers in 2017.

Roger Lorenzen is the current Athletic Director at Dayton. He was the principal when the cars were sent out to Rosario’s home to resurrect his football career.

“Thanks for remembering the small schools,” he wrote in connection with preparation for this story.

“Thank you,” I wrote back, “for sharing one of your all-time small-school greats with the rest of the state.”